Local News

the secret diaries of Pierre Trudeau’s former chief-of-staff provide a warts-and-all look at power

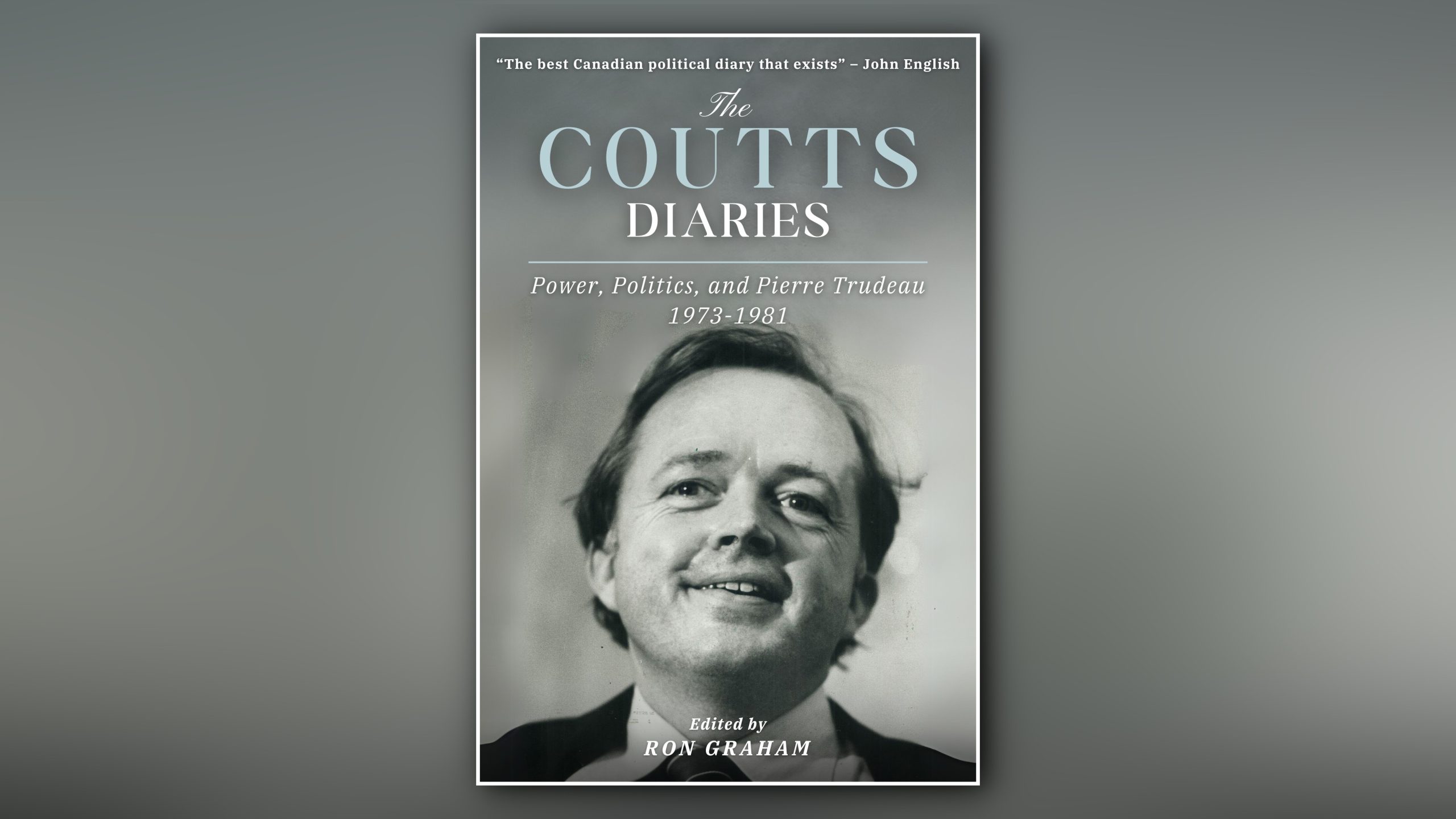

Jim Coutts served as Pierre Trudeau’s chief of staff during some of his most turbulent years as prime minister. It’s been said that Coutts not only knew everyone and saw everything – he wrote it all down. Now, nearly a dozen years after his death, his private observations are being made public in The Coutts Diaries: Power, Politics, and Pierre Trudeau, 1973-1981.

“Well, I knew that Jim had kept diaries. Nobody had ever seen them before, maybe a couple pages [were seen by] a couple of people, but they were sort of these mythic things,” said Ron Graham, who had the daunting task of going through the diaries and editing the entries for publication.

When Coutts died in 2013, he left his private papers to the Trinity College Archives at the University of Toronto with the proviso that the diaries are not opened until January 2025, what seemed like a remarkably brief amount of time to Graham.

“Usually, it’s 25 years or 50 years, and we’re not quite sure why Jim put such a quick turnaround, particularly since many of the people in the book are still alive,” he said.

The Coutts Diaries covers a period from 1973 to 1981, but Graham says the “mother lode” of material comes from six volumes covering 1979, 1980, and the first half of 1981.

This is familiar ground for Graham, who also edited The Essential Trudeau and two volumes of memoirs by former Prime Minister Jean Chretien.

Coutts provides some deliciously frank assessments of not only his old boss Pierre Trudeau, but of John Turner, Jean Chretien, and Paul Martin, among others.

“Jim had a reputation of being cherubic and fun and just great company, but he also had a dark side. He could be quite mean,” Graham said.

“So, I think people were expecting some really tough analysis of others. [But] I found that that his judgment was very close to accurate if you knew these people. And he was quite balanced in that way.”

Coutts was born in 1938 in High River, Alberta. He got his first job in politics in 1963, as the appointment secretary for then-Prime Minister Lester Pearson. So impressed was Pearson with the young Coutts, he even wrote about him in his memoirs years later, calling him “a very brilliant young man” and “wise in the ways of politics.” The two also bore a remarkable physical resemblance, so much so that Pearson feared people would think the country was being run by his grandson.

Coutts would return to Ottawa years later, this time to become political boss of Pierre Trudeau’s 1974 re-election campaign. The prime minister had been reduced to a minority government in 1972 and was eager to get back into majority territory. Thanks to Coutts, the narrative became less about the rising inflation and the stagnant economy of the time and more about leadership, pitting Trudeau against then-Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield. Coutts would become Trudeau’s principal secretary of chief of staff the following year. And he was still only 37 years old.

Coutts would end up having a front row seat to some pivotal moments of the Trudeau years. One example is the breakdown in the relationship between Trudeau and John Turner, who resigned as finance minister in 1975. Graham sees a parallel to Justin Trudeau and one of his former finance ministers.

“You know, if you live as long as I have, you go from being a journalist to an historian,” he said.

“I can watch some of these people like Bill Morneau and say, ‘Oh, if you had have known the John Turner story, you would not be doing what you’re doing, or you’d be doing it differently.’”

Coutts also provides an insider’s view of the 1974, 1979, and 1980 federal election campaigns, the separatist referendum in Quebec, and the patriation of the constitution. Graham says the entries are jaw-dropping, not only in their detail, but in how pertinent they remain, decades later. While the diaries were written 50 years ago, Graham feels they provide some surprisingly relevant insights for our current political age.

“My hope is that people will read it and see it as a master class of what to do or not to do in government because it’s all there. The mistakes are the same, the successes are the same, the issues are the same.”

“We’re in the kitchen of government here. You actually see how these things work. You see the problems. You see justice when you’re dealing with one thing, something else hits you, and it’s very, very hard complicated tough work.”

By the end of the book, Coutts is something of a sad figure. He devotes many entries to an unrequited love interest, his all-night poker games — both the wins and the crushing losses — and his failed attempts to transition from the backroom to the caucus room.

“It cost him big time by the end of his career because he lost twice when he tried to run for parliament, probably because of his public reputation, a reputation that was both too high for a backroom guy and also too controversial.”

Indeed, Coutts was equally admired and attacked for exercising more backroom power than anyone else in modern Canadian history. On a practical level, Coutts was instrumental in centralizing power away from cabinet ministers, members of parliament, and the public service into the Prime Minister’s Office.

“A lot of people go back to see Jim Coutts as the original sinner in terms of the centralization of the PMO, and the book suggests that there’s some truth to that. He had extraordinary access to the prime minister every day, he had extraordinary access to the ministers, to the cabinet, to every meeting going on, to every policy, to every bureaucracy,” said Graham.

“Most fantastically, I suppose, was when he got a $2 billion cut in the budget without telling the minister of finance and over the objections of the Clerk of the Privy Council. And he did that basically single-handedly, so he was not shy about using his power.”

But Graham says perhaps his greatest contribution was to persuade Pierre Trudeau not to retire to the countryside and raise his young sons after losing the 1979 election.

“Coutts, basically by himself, convinces Trudeau to come out of retirement to bring down the government of Joe Clark and fight the 1980 election. There’s a pivotal moment where it looked like Pierre Trudeau was going to announce his resignation, that he would not be running, and Coutts goes over to Stornoway in the morning, and basically spends an hour with him and convinces him to put his hat back in the ring,” he said.

“And that, of course, that led to fighting the referendum, that led to the Charter [of Rights and Freedoms], and it’s dramatic stuff, because it had epic consequences for the Canada we’re living in now.”

Graham says ultimately, The Coutts Diaries not only provides the reader with unvarnished takes on Trudeau and his contemporaries but also a very human look at power and politics.

“I think it’s refreshing for us to know that these people who are governing us are just ordinary people or maybe extraordinary people but with a lot of really ordinary neuroses.”

The Coutts Diaries: Power, Politics, and Pierre Trudeau, 1973-1981 is published by Sutherland House.